Mark Kersten adds to the discourse on the International Criminal Court and the “peace versus justice” debate.

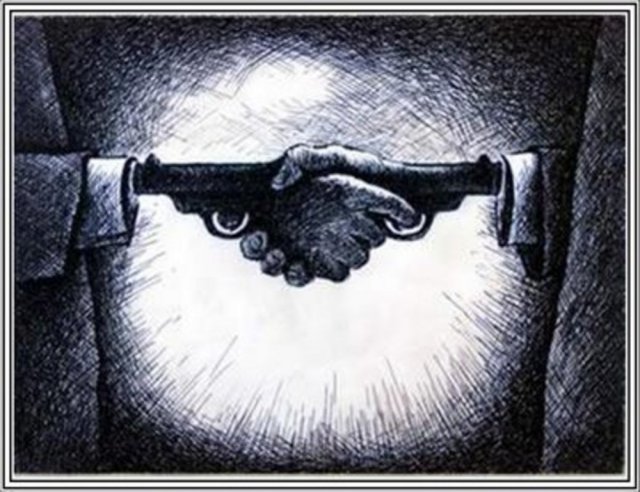

Few debates in international justice are as important yet inspire as much disagreement as the debate about the relationship between peace and justice. Should justice be pursued in response to mass atrocities when conflicts are still ongoing or when wars have only been recently concluded? Should peace and justice go hand-in-hand or should justice always follow peace? Does a moral, legal and political obligation to victims and survivors who demand accountability trump the possibility that justice may complicate conflict resolution? Will bringing perpetrators of mass atrocities to justice ultimately help or hinder efforts to build and maintain peace?

These questions arise in the so-called “peace versus justice” debate, which has gained notoriety with the establishment of the permanent International Criminal Court (ICC) and increasing expectations that international criminal justice institutions will act as ‘first responders’ in emerging conflicts. Almost fifteen years have passed since the creation of the ICC, yet it remains difficult to maintain that we’re much closer to a conclusive verdict as to the relationship between international criminal justice and the pursuit of peace. Every time reports emerge that the ICC might become active in an ongoing and active conflict, both sides of the peace-justice debate rehash and recycle their claims: the Court will ruin any prospects for peace or, without the Court, meaningful peace is a pipe dream. The current state of the debate needs fresh thinking and a renewed appreciation of the complexity of issues at play when the ICC investigates and prosecutes belligerents in active conflicts. Focusing so singularly on the ICC’s effects at the expense of the broader political factors and conflict dynamics at play has entrenched rather than alleviated the harshly dichotomous nature of the peace-justice debate. There is a need to see the forest for the trees.

So what, if anything, have we learned about the ICC’s impact on conflict resolution and peace-building? In this brief article, I would like to assess some of the challenges confronting a more accurate and nuanced understanding of the ICC’s effects on peace and then offer some thoughts stemming from my own research on the peace-justice debate, recently published in a book entitled ‘Justice in Conflict - The Effects of the International Criminal Court’s Interventions on Ending Wars and Building Peace’.

There is no doubt that the International Criminal Court is a unique entity. It is, at once, both an international organization, whose existence and operations depend on the support of states, and an international court with a mandate to pursue justice for the worst crimes known to humankind. As such, it treads — often uncomfortably — at the nexus between politics and law. Its staff insist that the Court’s involvement in conflict situations are merely an expression of its legal mandate. It does not practice politics. This position plays down the controversial role of the Security Council in issuing highly-politicized referrals of situations to the ICC in response to breaches of the peace — most notably by prohibiting the ICC from investigating citizens of non-member states, of which there are three on the Council (China, Russia, and the US). This mantra also lies at the heart of how the professionals that make up the ICC see their role in contributing to peace. Former chief Prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo and current Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda have insisted that there must be a division of labour between the pursuit of justice and the pursuit peace. The Court is responsible for the former; other institutions, like the United Nations Security Council, are responsible for the latter. At the same time, however, they insist that there cannot be a credible or durable peace without justice and that, in cases in which the ICC has influenced a peace process, as in northern Uganda, its impacts have been positive. This contradictory posture — that peace is none of the ICC’s business, but peace is impossible without the Court — belies a significant problem: no one in the ICC’s Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) or any other organ of the Court systematically assesses the institution’s impact on peace processes.

To those who view international criminal justice processes as having a role to play in atrocity responses and prevention, it remains frustrating that the ICC itself does no stock-taking of the impact it has on the conflicts in which it intervenes. As a result, whatever the ICC learns from its previous interventions depends wholly on the feedback it receives from third-parties — diplomats, NGOs, and academics. The Court’s staff may argue that this is not part of their mandate. However, this is a spurious claim. The ICC consistently speaks of its indispensability in establishing peace. It also regularly creates roles for itself outside of its strictly judicial purview, such as strengthening the ability of domestic judiciaries to prosecute international crimes themselves.

Another possible reason for the Court’s reluctance to stock-take its impacts is likely to be that the institution doesn’t have sufficient resources to dedicate to such stock-taking. This too is unsatisfactory. If resources are the problem, the Court can and should push for additional funding from member-states. There is nothing costlier to the legitimacy of the Court than repeating mistakes and feeding the acrimony of those who believe the ICC has no place operating in ongoing conflict situations in the first place. Learning how the Court affects conflict and peace processes isn’t just about making peace more likely or justice less disruptive; it also holds the promise of making the pursuit of accountability more effective and efficient.

There is also a danger in relying on third parties to understand how the ICC affects peace and conflict processes, namely that it permits the avoidance of inconvenient truths by fostering a cherry-picking attitude to evidence. Much research on the peace-justice debate continues to occlude rather than elucidate the effects of the ICC. This is true of studies that critique the Court’s ability to contribute positively to conflict resolution and peace as well as those that seek to lend credence to the Court’s virtues.

Many of the ICC’s critics often recycle intuitive but speculative claims, insisting that any and all targets of the ICC will inevitably “dig their heels in” and have little choice but to fight to the bitter death. In doing so, these detractors reduce all actor types — heads of state, senior officials, rebel commanders, militia leaders, and the various rank-and-file — to the same, basic set of incentives towards the ICC and resolving the war in which they act as belligerents. Reducing complex and different types of actors risks severely over-simplifying the psychology and incentives of warring parties. A rebel leader like Joseph Kony of the Lord’s Resistance Army is not the same kind of actor as Muammar Gaddafi, the former head of state of Libya. Yet critics assume that they follow precisely the same logic: if the all-mighty ICC targets them, they will fight to the death and never agree to peace.

Others criticize what they see as the hegemony of retributive, international criminal justice impulses and models. They insist that reconciliation, restorative justice, and truth-telling are more appropriate means of building long-lasting and meaningful peace. Yet, while there is little doubt that a more “holistic” approach to transitional justice is wiser than any singular dependence on retributive accountability, criminal accountability is a growing expectation of victims and survivors of mass atrocities. Who will ignore their voices in favour of transitional justice mechanisms that privilege stability over transformation and, all too often, offer what amounts to impunity to perpetrators of mass atrocities?

The claims of proponents are also often unhelpful. Many seem more interested in writing the benefits of international criminal justice into reality than in conducting rigorous on-the-ground empirical research. Weak correlations are dressed up and presented as strong causal claims whilst offering no theory of the mechanisms by which these purported effects are produced. This is particularly true regarding the ability of the ICC to marginalize leaders and deter mass atrocities. Such claims are typically located in quantitative studies by scholars who seem unable or unwilling to engage with local actors and data. We are thus told that the ICC galvanizes local justice in the situations in which it intervenes simply because those states hold trials — with little consideration that they may be sham or show trials. We are shown how decisions at the ICC interact with levels of violence in conflicts, without evidence indicating that warring actors are following the day-to-day actions made by Judges and prosecutors at the ICC. And we are told that the ICC exerts a clear deterrent effect based on findings that if agents of a non-member state killed 1000 people whereas agents of a member-state killed only 999, then the ICC’s deterrent impact must be real.

The situation in Libya offers a compelling case study for the limitations of these polar positions and the importance of more nuanced approaches to the peace-justice debate. In 2011, the ICC was requested, on behalf of the UN Security Council, to investigate allegations of war crimes and crimes against humanity in Libya. Critics of the Court immediately insisted that such an intervention would derail any peaceful solution to the Libyan civil war by pushing Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi — a target of the ICC — into a corner from which only violence offered him a way out. Sanction by the Court, they exclaimed, would leave Gaddafi with no choice but to fight to the death. The ICC and its champions, in contrast, saw the chance for the Court to ride the near-universal condemnation of the Gaddafi regime and to positively influence the civil war in Libya. Neither side was right.

There is no evidence that the ICC has done anything to positively influence peace in Libya — during or since the civil war concluded in October 2011. But neither is there evidence that the ICC made Gaddafi commit to a violent, military resolution to the war. Indeed, the dictator appears not to have concerned himself at all with his indictment by the ICC. This should be unsurprising given that events on the ground posed an existential threat to his four-decade long rule and his life itself. If anything, the ICC made opponents of the Gaddafi regime commit to a military solution to the conflict.

Lessons in making more modest claims regarding the ICC’s effects can also be gleaned from situations in which the ICC has not intervened. Take, for example, the situations in Syria and South Sudan. Both conflicts have been characterized by large-scale violence orchestrated by high-level political figures, mass atrocities amounting to war crimes and crimes against humanity, and bouts of failed peace negotiations. Despite overwhelming evidence of mass atrocities, neither situation has been investigated by any international tribunal, let alone the ICC. Yet the same doomsday scenarios that ICC critics predict will transpire if the Court intervenes in conflict scenarios continue to be evident without an intervention: large-scale violence, mass atrocities, and failed peace negotiations. While it certainly does not follow that conflict resolution or peace-building in these situations would necessarily benefit from the ICC’s involvement, this should, at the very least, give critics of the ICC pause. It should also inspire more sober assessment of what the ICC can, and cannot, achieve.

Put another way, in those situations in which ICC champions have had their chance, like Libya, no clear peace dividend emerges from the Court’s involvement. But, in those cases in which critics have had their way, and no ICC intervention has transpired, the absence of international criminal justice hasn’t advanced peace or prevented violence. This should give both sides reason to re-evaluate their dogma as well as the assumptions they bring to bear in their assessments of the ICC’s impacts.

Of course, there is a wealth of remarkable and important research on the ICC’s effects. New, fine-grained studies on how deterrence affects rebels on the ground, new thinking that directly challenges causal claims, and novel research agendas focused on the ability of the ICC to affect actors before it issues arrest warrants all point to the possibility of a richer and more nuanced body of work exploring the peace-justice relationship. Crucially, such examinations share an appreciation for the limits of what the ICC is and what it can achieve. They acknowledge that the ICC is here to stay. But the effects of its brand of justice need to be understood, its past blunders avoided, and its successes fostered.

Perhaps this is the greatest lesson for those engaged in the debate about the effects of the ICC on peace processes: the ICC is neither as good as proponents think it is nor nearly as bad as critics believe it to be. It is certainly not as potent as either side of the debate insists. This is evident in those situations in which the ICC has been active as well as those in which the Court has not.

The ICC is now one of a diverse array of international actors operating in response to violent political conflicts. It works within a context characterized by a myriad of conflict causes and political dynamics. It would be disingenuous to suggest that any new actor in such cases could ever avoid complicating conflict resolution and peace-making. That does not necessarily mean that peace is impossible when the Court intervenes. What it does mean, however, is that scholars, policymakers, diplomats and the ICC itself need to do a better job in assessing the Court’s impacts. A good place to start would be by seeing the forest for the trees.