Salt comes from the north, gold from the south, and silver from the country

Of the white men, but the word of God and the treasures of

Wisdom are only to be found in Timbuktu.

—West African proverb

The International Criminal Court has taken a critical step in protecting the “wisdom” of Timbuktu, and, by extension, providing legal protection for cultural heritage everywhere. In a historic case, the ICC will try Ahmad al-Faqi-al-Mahdi as a war criminal for allegedly causing damage to a mosque, shrines, and manuscripts in Timbuktu. For the first time, the destruction of cultural heritage will be considered by ICC judges as a war crime, setting a precedent with far-reaching ramifications. Mark Ellis, chief executive of International Bar Association, captured the significance of the ICC’s action: “ ….the destruction of cultural heritage is not a second-rate crime. It’s part of an atrocity to erase a people. I hope it will act as a deterrent to similar acts in other countries.”

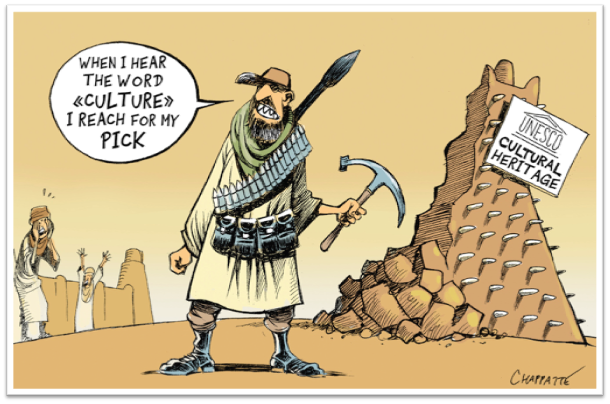

The extremists who invaded and occupied Timbuktu in 2012 fully understood the importance of culture—past and present—as the foundation of the fabled desert city’s identity, pride, and social cohesion. To subjugate the population and to impose their Wahabi-inspired nihilistic version of Islam, they destroyed historic buildings, torched precious manuscripts, and banned music—the lifeblood of Mali. Timbuktu may sound remote, even mythical, but the humanistic ideas and atmosphere of tolerance that flourished there have universal and timeless relevance. Even more immediately, Mali’s music, brought to the United States by slaves, seeded the blues and rock ’n’ roll.

Known as the city of 333 saints, Timbuktu leveraged its position as a crossroads of trade, particularly gold and salt, to become the intellectual capital of the Muslim world. A center of learning from the 12th-16th centuries, on a par with Bagdad in the east or Florence in the west, Timbuktu attracted 25,000 students to its universities—more than the city’s population today. During Timbuktu’s Golden Age, scholars produced hundreds of thousands of manuscripts exploring every topic imaginable, including astronomy, biology, ethics, human rights, women’s rights, jurisprudence and good governance, literature, poetry, and music. Not exactly what much of today’s discourse on Islam would lead us to expect from Islamic scholars. Timbuktu itself, with its breathtaking historical architecture, treasure trove of manuscripts, and vibrant, living culture of music, stands as an authentic Islamic counter-narrative to violent extremism.

How ironic then that Timbuktu fell prey to Islamic jihadists, whose fundamentalist interpretation of Islam could not have contrasted more with the tolerant, Malikite version of the faith practiced in Timbuktu. The invaders imposed a brutal version of sharia law—persecuting women and meting out cruel punishments, including chopping off limbs. Thanks to the resilience and resourcefulness of the local population, and to the intervention by French-led forces, the damage during the 2012-13 occupation was not as catastrophic as it could have been.

Although several thousand manuscripts were burned, more than three hundred and fifty thousand were saved. In an ingenious operation led by Dr. Abdel Kader Haidara, the manuscripts were spirited away under the very noses of the extremists and transported to Bamako. There they will remain for the immediate future while their contents are digitized—an impressive operation overseen by Dr. Haidara’s non-profit Savama DCI and supported by a host of international donors.

But the invaders did serious damage to the shrines in the cemetery at the entrance to the town, places of regular pilgrimage for a people who venerate their ancestors and deceased relatives, and who revere the scholar/saints of Timbuktu’s past. The extremists objected to worshipping anything or anyone outside their narrow definition of Islam.

“The mausoleums represent the soul of Timbuktu. They form the foundation of our identity,” the imam of the Djinguereber Mosque told me. The shrines are dedicated to the city’s greatest scholars and saints. (So much was knowledge valued in Timbuktu that the lines between mortal scholars and saints are blurred.)

For Manny Ansar, founding Director of Timbuktu’s renowned Festival Au Desert, which drew thousands of fans and musicians including Bono, Jimmy Buffet, and Robert Plant to listen to and jam with Mali’s music greats, the mausoleums represent a historic symbol of his cultural patrimony. The origin of the mausoleums stems from Timbuktu’s nomadic past, when Bedouins would mark the graves of important figures with large stones so that worshippers could find the spot amidst the vast shifting sands of the desert.

The buildings themselves—simple, unadorned mud brick buildings—are unimpressive architecturally. But it is the symbolic value of the shrines as the living testaments to Timbuktu’s history that matters to the local inhabitants. Attacking the shrines was like attacking the ancestors of the Timbuktuans.

Ambassador Schneider, third from right, with the guides, historians, and traditional builders from Timbuktu in front of the shrine they restored.

Fortunately, Irina Bokova, Secretary General of UNESCO (who has also contributed an article to this Arguendo roundtable), understood the value of these simple structures to the traumatized inhabitants of Timbuktu, not to mention the world. She noted that “[a]ttacks against cultural heritage are attacks against the very identity of communities. Attacks on the past make reconciliation much harder in the future.” Bokova raised funds from a host of international donors to have the shrines rebuilt, following traditional techniques. Together with the Imam of the Djinguereber mosque, she celebrated the inauguration of the reconstructed shrines in July of 2015.

Rebuilding the shrines represents an important first step towards restoring Timbuktu’s spirit, but the damage wreaked by the extremist occupation will not be undone until tourism returns, bringing with it essential economic revitalization. The Timbuktu Renaissance (TR), a Malian-American initiative that aims to foster peace, unity, reconciliation, and economic development in Timbuktu and Mali through a focus on culture, is pursuing various strategies to promote peace and unity and to jumpstart revenue-generating cultural activities.

For the people of Timbuktu, culture is as important as the air they breathe. When told of the occupiers’ ban against music, Fadimata Walet Oumar, lead singer of the Tuareg musical group Tartit, declared, “[t]hey’ll have to kill us first.” Manny Ansar informed me that although some in Timbuktu find it strange that a trial about cultural heritage is taking place before anyone has been held accountable for the human rights abuses during the occupation, Timbuktuans, nonetheless, welcome the global recognition of the seminal importance of their city’s knowledge, culture, and art that bringing Ahmad al-Faqi-al-Mahdi to justice provides.

As the world’s cultural heritage is being systematically attacked by ISIS, the ICC case against Ahmad al-Faqi-al-Mahdi sets an essential precedent. Hopefully, other perpetrators will be captured, and still more will be deterred before more irreplaceable testimonies to our civilization are destroyed.